Iola Lenzi invokes the enduring words of Fyodor Dostoyevsky from his 1869 novel The Idiot: “Beauty will save the world.” In this phrase, beauty transcends the aesthetic—it becomes a moral and spiritual force, capable of redeeming humanity. Dostoyevsky, who himself weathered the storms of a turbulent life, offered light to suffering souls through the redemptive power of his stories. In much the same way, the 8 Southeast Asian artists in Lenzi’s curated exhibition channel their own trials into works of quiet resistance and luminous hope. Amid the shadows of their lived realities, beauty still blooms—fragile, defiant, and deeply human.

Dinh Q. Lê (Lê Quang Đỉnh) 黎光定

A vibrant artwork boldly exposes a harsh reality.

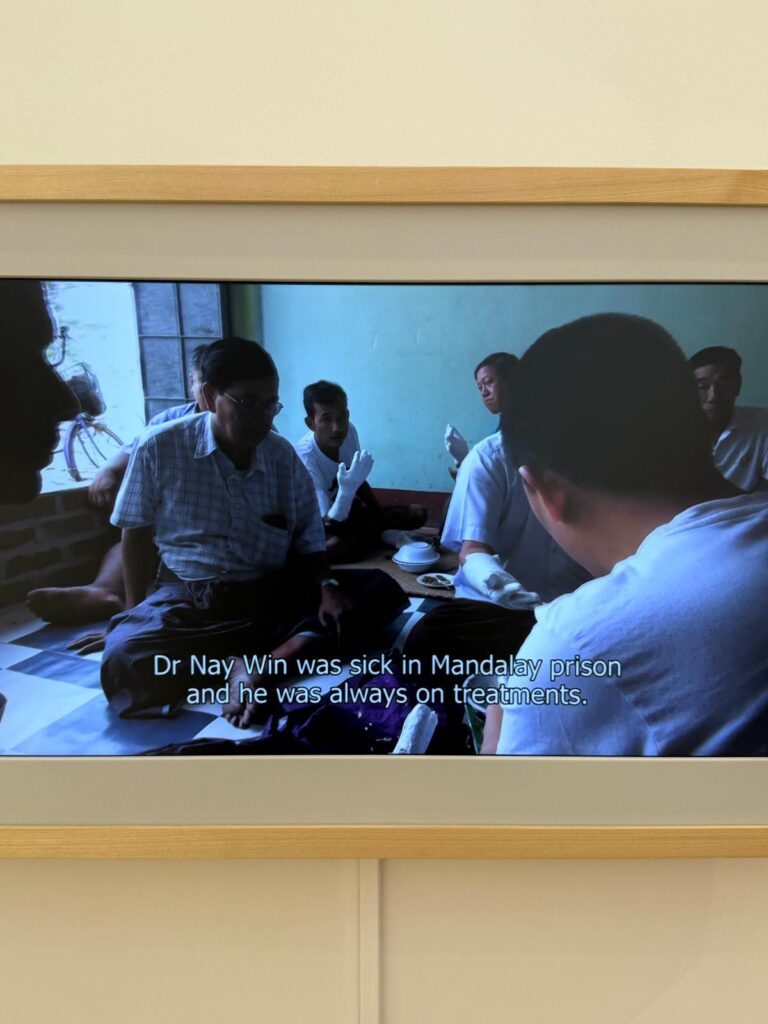

Dinh Q. Lê’s video work forces us to confront Gary Glitter’s crimes: in the 1970s, Glitter sexually harassed three underage girls in Vietnam. The bitter irony is that, at the time, Vietnam seemed powerless to shield its own children—a failure underscored by Criminal Code Article 142, introduced only in 2015 after Glitter’s conviction, yet still leaving legal ambiguities that could permit similar abuses.

A vibrant artwork boldly exposes a harsh reality.

Dinh Q. Lê’s video work forces us to confront Gary Glitter’s crimes: in the 1970s, Glitter sexually harassed three underage girls in Vietnam. The bitter irony is that, at the time, Vietnam seemed powerless to shield its own children—a failure underscored by Criminal Code Article 142, introduced only in 2015 after Glitter’s conviction, yet still leaving legal ambiguities that could permit similar abuses.

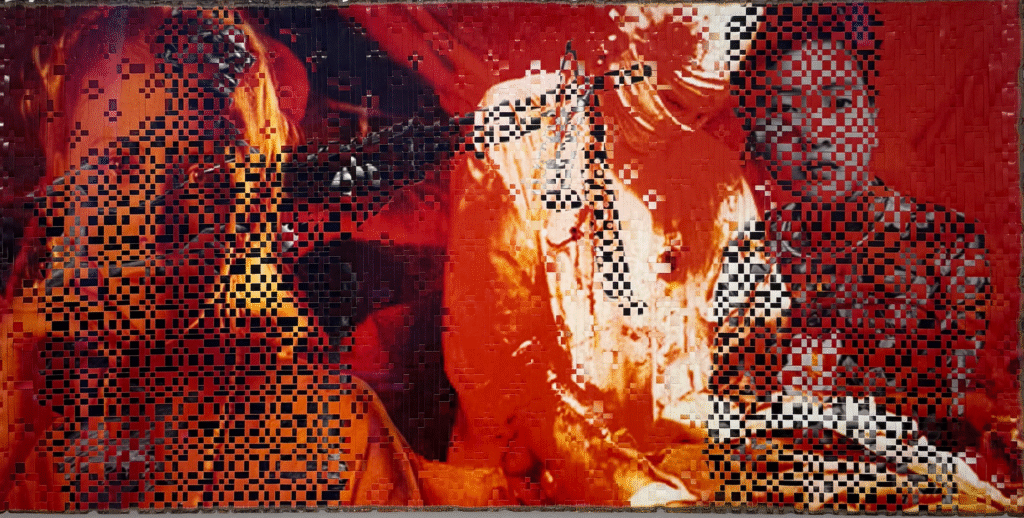

Untitled 10 (from Vietnam to Hollywood Series), 2004, c-prints and line tape, 85 x 171 cm

Meryl Streep from a Hollywood Movie (Left); Nam Phương, the last empress consort of Vietnam (right)

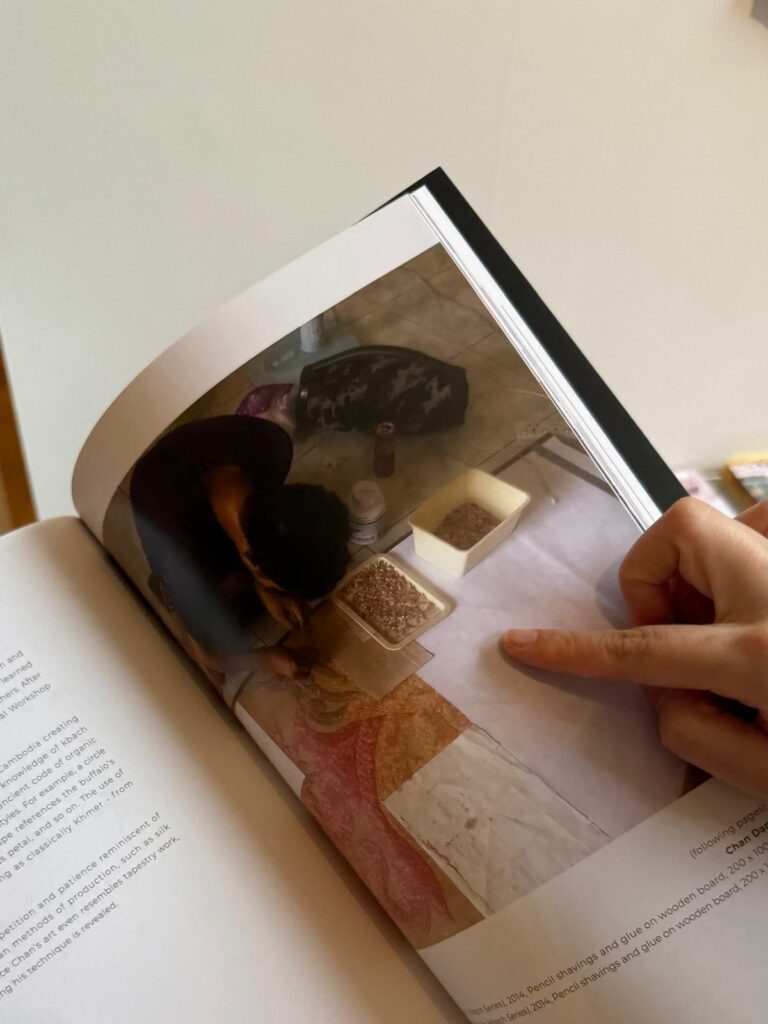

Since the late 1990s, Dinh Q. Lê has been crafting his own visual language. Drawing on the vernacular mat-weaving techniques of his rural southern childhood, he pioneered a photo-collage method that threads cinematic fiction and archival truth into a single frame. In his From Vietnam to Hollywood series, Hollywood’s grand narratives intertwine with raw historical images to offer Vietnam War stories from both American and Vietnamese perspectives.

As outsiders bearing witness, our perceptions shatter and layer like memory—always pieced together from the many fragments we encounter. Through Dinh Q. Lê’s art, we’re reminded that to remember is to navigate complexity, and that every new frame reshapes our view of the past.

Bùi Công Khánh 裴公卿

Whose grandfather is ethnically Chinese, the artist Bùi Công Khánh lives in Hội An—a city where Vietnamese and Chinese cultures intertwine. Yet in recent years, the ties between these two nations have shifted, forged less by shared heritage and more by the cold mechanics of politics, military strategy, and economic ambition. In Bùi’s work, this tension is rendered with haunting clarity: metallic hearts float atop a blue-and-white porcelain-like background, pierced by fine red lines. These lines, delicate as blood vessels, speak of a shared lineage. But they run cold, echoing the superficiality of a relationship built on power rather than kinship.

Southern Chair (2018) (left); The Wonnd has Not Healed (2018) (middle); Northern Chair (2018) (right)

This duality continues in Bùi’s sculptural furniture, a fusion of Vietnamese and Chinese aesthetics. The piece is the second of his carved art I’ve encountered—the first i encountered at M+ Museum. Made from jackfruit wood, a material favored by the Central Vietnamese middle class for its durability and resistance to insects, the craftsmanship is meticulous, demanding time, labor, and devotion. Two chairs flank a table, each bearing emblems that hint at opposing ideologies—North and South. Though they face the same direction, they are divided not only by the table but by the weight of history and politics. The furniture is adorned with cruel symbols: grenades, medals, pistols, barbed wire. What appears at first to be a warm, traditional domestic setting is invaded by instruments of violence—an unsettling collision of the intimate and the militaristic.

Porcelain Medals (2018)

In front of this furniture ensemble stands Porcelain Medals (2018). Once symbols of pride, identity, and sacrifice—worn on the shoulders of soldiers and celebrated in the name of nationalism—these medals are now rendered in fragile porcelain. Their meaning, once so loudly proclaimed, has become brittle, hollow. Stacked like anonymous bodies on a battlefield, they seem to mock the very notion of heroism. Bùi’s work questions the legacy of civil war, the glorification of violence, and the absurdity of valor defined by the state. To those outside the machinery of power, these medals are no longer sacred—they are relics of a broken promise.

Vũ Danh Tân 武民新

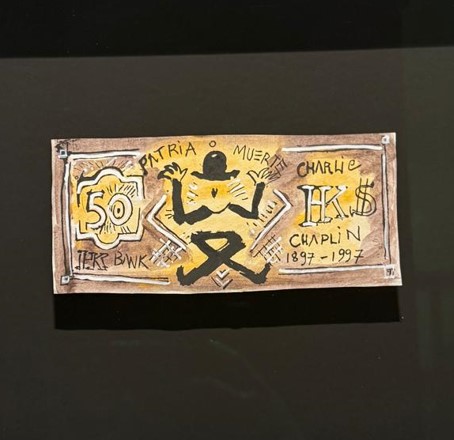

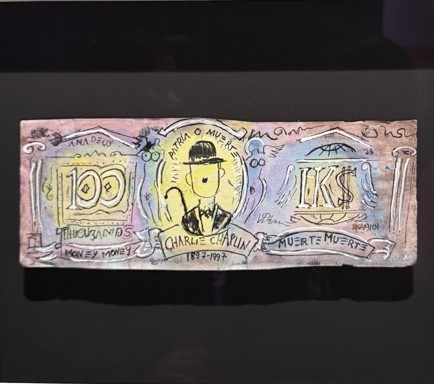

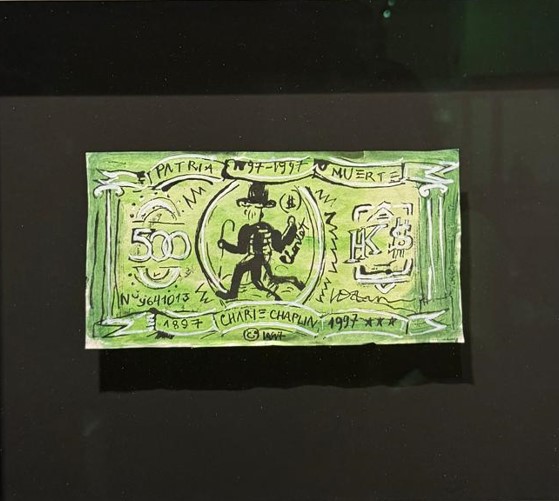

Vũ Dân Tân’s work interrogates the nature of money—not as a vessel of intrinsic worth, but as a symbol of national identity, power, and control. Currency, though ostensibly neutral, becomes a tool of division, separating people into imagined communities defined by borders and banknotes. Also, In the wake of Vietnam’s Đổi Mới reforms in 1986, the country shifted from a state-controlled economy to a socialist-oriented market system. With this transformation came the influx of capitalism and consumerism, reshaping not only the economy but the cultural psyche.

In one of his most striking gestures, Vũ emblazons an iconic English actor—Charlie Chaplin—onto a Hong Kong dollar of his own creation. The irony is layered: Chaplin, though British, lived in the United States; Hong Kong, once a British colony, pegs its currency to the U.S. dollar. This triangulation of identities and economies underscores the absurdity and arbitrariness of monetary systems, revealing how deeply entangled they are with histories of colonisation, migration, and global capital.

And yet, within this ironic currency, Vũ offers a quiet tribute. Echoing Dostoevsky’s belief that “Beauty will save the world,” Charlie Chaplin—gentle, dignified, and resilient—embodies the enduring power of kindness amid hardship. In Vũ’s hands, Chaplin becomes a symbol not just of irony, but of hope circulating within systems built on control.

Other Artists