I recently visited Villepin for their latest exhibition, Worlds Within: Art as Refuge, a contemplative journey through the works of four artists from across the nations: Zao Wou-Ki, Fernando Zóbel, Lê Phổ, and Kang Myonghi. The exhibition weaves a narrative of how each artist turns to art as a refuge for identities, memories, and beauties.

After ascending the stairs to the floor devoted to Lê Phổ, I found an intimate-sized Mother and Child hanging beside a small “window,” inviting me to peek through its flame into a tranquil garden where a mother and son study together.

Peace. A rare peace, often absent in busy Asian homes where mothers tighten their voices over homework. Here, silence itself feels sacred—a gentle space for mother’s love.

Reverence for Chinese Artistic Traditions

Mandarin Ducks and Lotus with a sofa lies beneath—another Lê Phổ revelation. The deep brown background that Lê Phổ painted recalls the aged silk of classical Chinese scrolls, while the open space (“liubai” 留白) in the top right corner magnifies the presence of ducklings nestled among floating lotuses. It evokes the impressions Lê Phổ absorbed during his 1934 studies in Beijing.

Though motherhood does not preside here, another intimate bond unfolds in the ducks’ lifelong devotion. An eternal love with lotuses gather in the quiet grace cradle love untainted.

Synergy Among Three Cultures

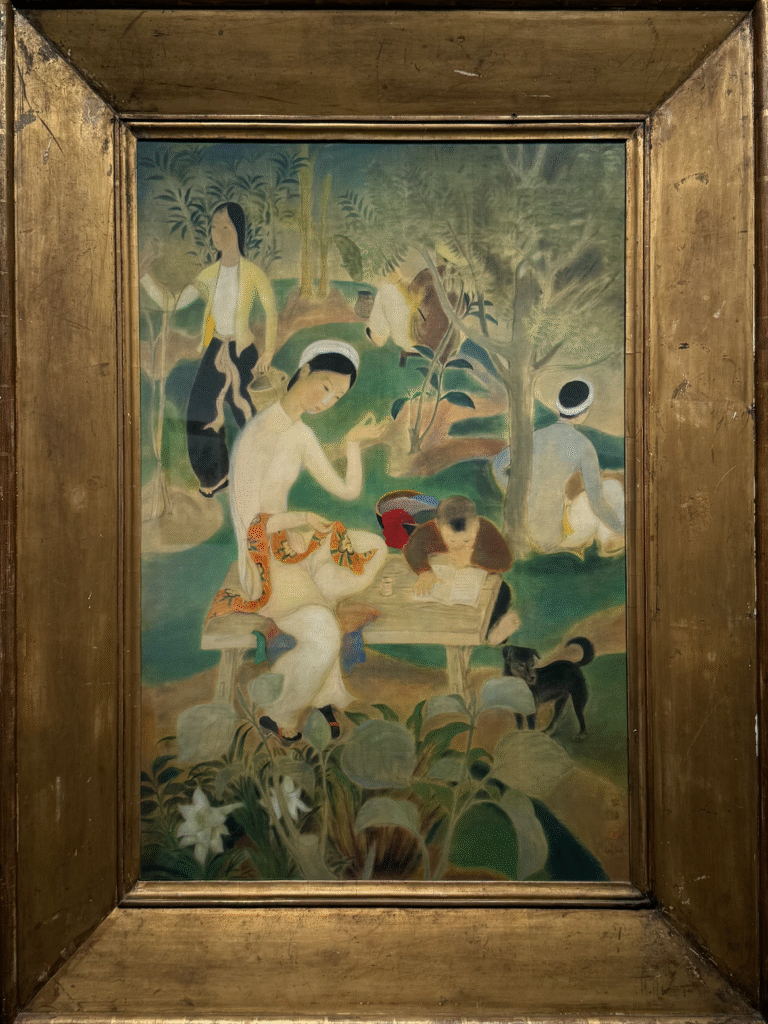

On the adjacent wall, another canvas La Famille Dans Le Jardin reveals a winding path beside a river—echoing a Chinese shanshui scroll: asymmetrical, unpredictable, yet vividly alive. I trace its curves behind the lilies until I encounter, once again, a mother stitching while her son reads beside a black Bắc Hà puppy. No scolding, no raised voices—just figures quietly absorbed in their own rhythms, sharing a public oasis of stillness.

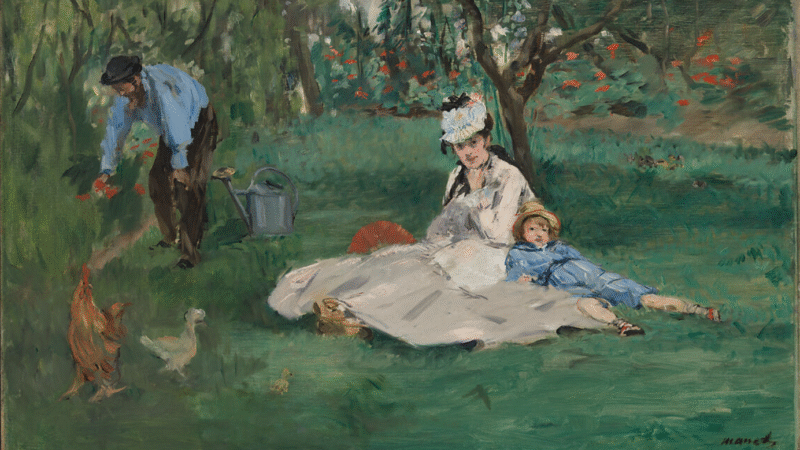

Painting everyday life outdoors was a pursuit of the impressionists, naming Monet, Manet, and Renoir. Lê Phổ, among the first graduates of EBAI under director Victor Tardieu, inherits that lineage but roots it in Vietnam: villagers collecting water, fishing along shaded banks, resting beneath trees.

This painting is the most valuable Lê Phổ in the world—not only for its auction price (HK$18.6 million / US$2.4 million), but also for the delicate way it expresses his yearning for his Vietnamese roots, his dialogue with Chinese art, and his admiration for Impressionism.

Rooted in Soil, Blossoming Across the World

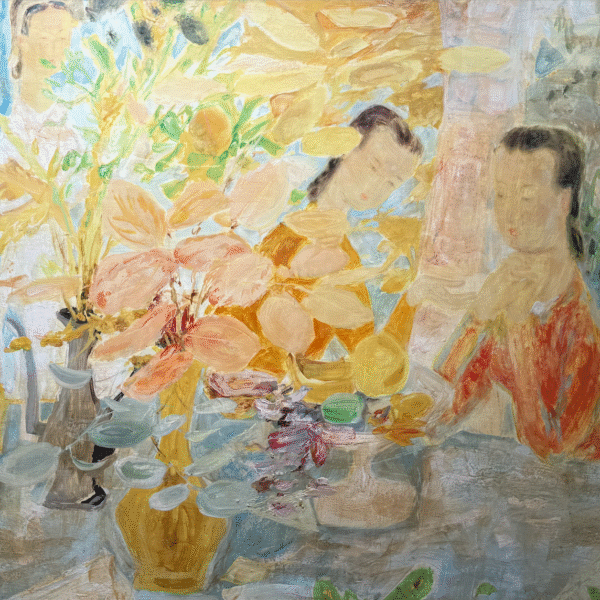

When flowers leave their native soil and settle in a new vase, they rewrite their story—and so did Lê Phổ. In 1937 he planted himself in France, soon collaborating with Galerie Romanet (1946–1962). His still lifes from this era layer rustic impasto backgrounds behind central bouquets. One oil-on-silk stunned me: its texture evoked tempered chocolate on marble, and I almost thought Lê Phổ used a marker to sign on the painting.

In the inner gallery, Les Jeunes Filles à la Coupe de Fruits recalls his Findlay Gallery period (from 1963), when he followed his peer Vu Cao Đàm to the Wally Findlay Gallery in the US. The canvas shimmers with warmer hues, hazy brushstrokes, and edges glowing like a sunlit afternoon seen through a misted lens brushed with a thin layer of Vaseline. As written in the Villepin catalogue, Lê Phổ’s work radiates an “emotional temperature.” I stood at 3pm in a sun-drenched garden perfumed by flowers, where summer breezes whispering through leaves, birds chanting, butterflies fluttering—and in that moment I sense the purest joy.