I can hear the soft rhythm of wooden blocks echoing in my mind as I gaze upon Đoàn Văn Tới’s silk paintings. Misty, calm, and meditative — his work breathes with a calmness that mirrors his own diffident presence. Tới’s art is not merely visual, it is a gentle whisper of his inner world, a reflection of his Zen Buddhist practice.

In 2024, over 60 works have been completed for the Karaoke Karaoke series, averaging nearly one artwork per week. This count excludes pieces without a mark of date on the website and his numerous side projects, the actual number may be even higher. It’s a remarkable testament to his discipline and productive life.

Presented by Indochine House in Hanoi and most recently featured in the group exhibition Ceci N’est Pas Une Guerre – This Is Not A War at Eli Klein Gallery in New York, curated by Đỗ Tường Linh. Thanks to an introduction by Bach, I was fortunate to visit his studio — a serene space where silk, thread, and thought converge — and ask the questions that had lingered in my mind since encountering his work last December.

His art, to me, is a sutra, reveals the truth of Buddhism through the series.

Compassion: the Core Element in the Path of Enlightenment and in Tới’s Art

In the Red River series, Tới draws from a poignant scene: bathers in the river — workers from Dong Xuan market, the homeless, and the affluent — taking off their clothings, their accessories, their symbols of status and desire, to bathe together. In this shared vulnerability, he saw a metaphor for equality. The river, like compassion, washes away illusion and reveals the sameness beneath.

In a later series Karaoke Karaoke, a stitched skeleton speaks the same truth. Strip away flesh, beauty, and perception — we are all made of 206 bones. Tới continues this quiet dissection, moving from bodies to skulls to the invisible particles of air, each element a reminder of our shared origin and impermanence.

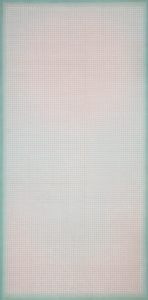

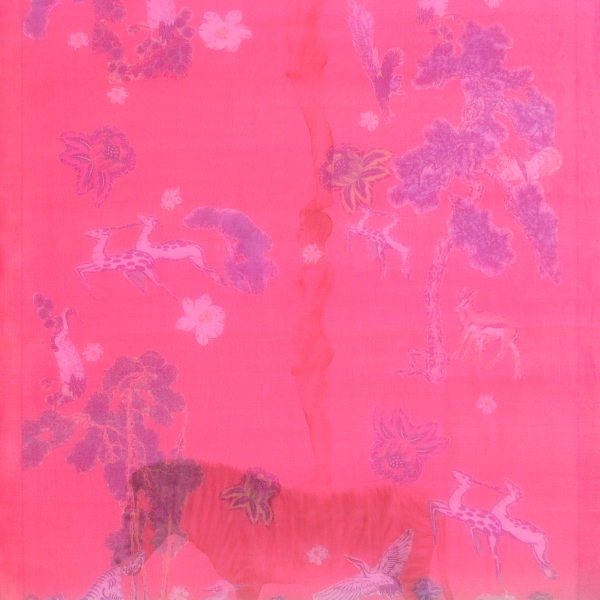

His technique echoes this philosophy. He cuts fabric and re-stitches it onto silk, scattering fragments like lives across the canvas. Yet the silk — soft, translucent — overlays the chaos, blending jagged edges into harmony. It is a metaphor for compassion itself: the understanding that all lives are equal and deeply interwoven. The joy or suffering of one ripples through the whole, and the choice to respond with care becomes a sacred act.

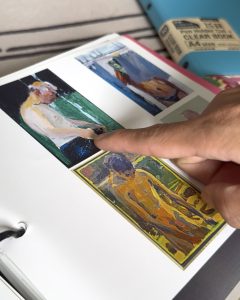

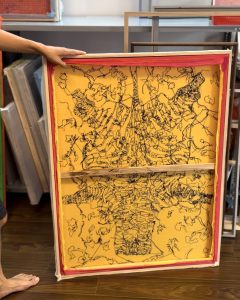

Before (left) and after (right): upper silk layer added over stitched underlayer.

Once the Thread Comes Off, Everything Falls Apart

In his Gia Đình (Family) series, Tới revisits the traditional Vietnamese family portrait — a formal composition where elders sit at the center, flanked by generations in hierarchical order. These portraits, once rare and costly, were occasions to display one’s finest attire and affluence.

But Tới removes individuality from the faces, rendering them nearly identical. Behind the silk, a single thread links each figure — a quiet symbol of bloodline and familial bond. Without it, the image would unravel. It is a meditation on connection: fragile, essential, and often invisible.

All starts from the self-compassion

Compassion, Tới believes, is not bestowed by divine intervention but cultivated through practice and awareness. In one of Buddha’s teachings, students are invited to support each other while crossing a river. They learn that to help others, one must first find balance within.

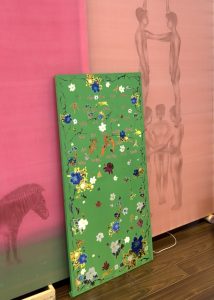

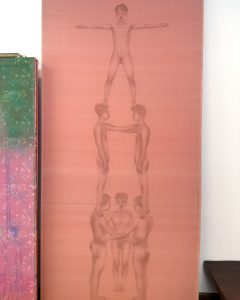

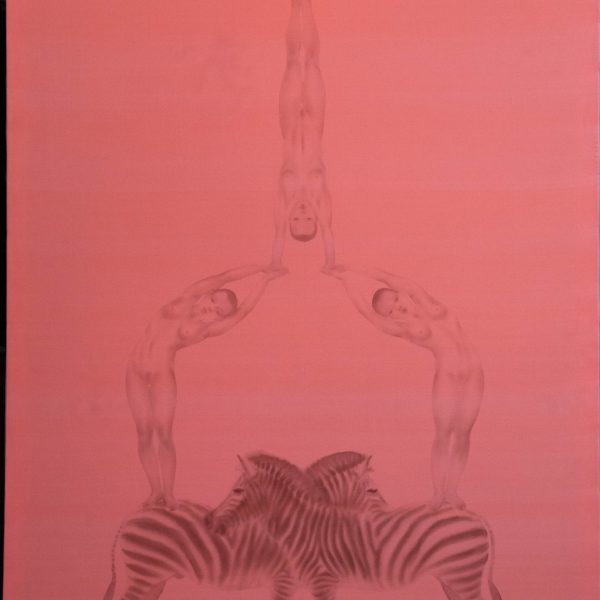

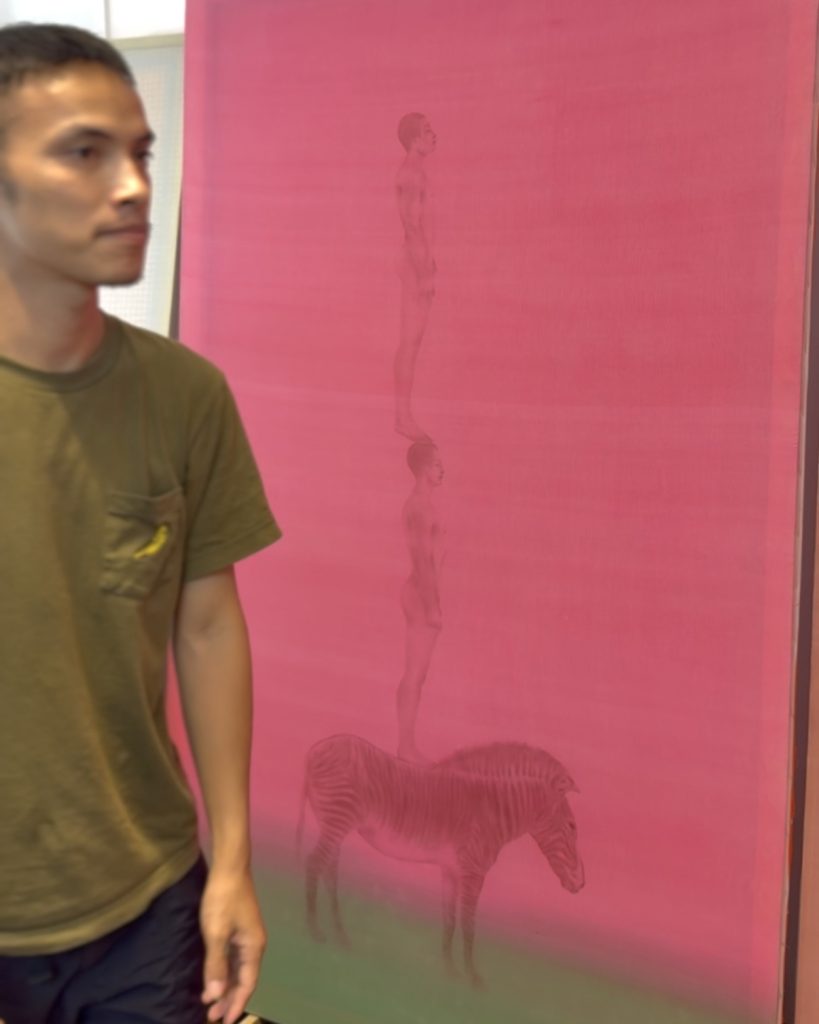

This lesson finds form in the Gate Gate series, where humans perform acrobatic feats beside a zebra — a creature both wild and trainable. The zebra, like our thoughts, is restless. Yet with gentle guidance, it learns to move with grace. The performers, too, must find equilibrium to support one another. Compassion begins with presence.

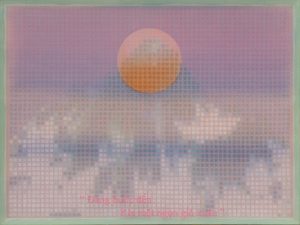

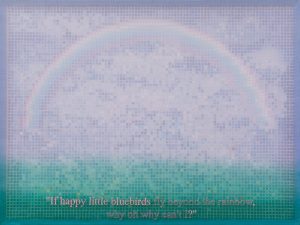

Everything begins within — when infused with awareness of the Buddhist truth, even the seemingly nonsensical poem or lyric could become a sutra. For Tới, meaning is plastic, we hold the autonomy to shape the words we choose.

“Why Did You Paint a Zebra?”

The zebra, Tới explains, is inspired by the Chinese metaphor 心猿意馬 [the monkey mind and horse will]. Meditation, he says, is not stillness but a dance with restlessness. Our minds leap like monkeys, our intentions gallop like horses. The goal is not suppression, but gentle redirection.

Quoting Đức Phật Thích Ca: “Do not cling to the past, do not chase the future, see everything fully in the present as it is.” Tới embraces the discursive mind, likening meditation to taming — not tying down — the monkey and horse.

The zebra, wilder than a horse, lives among lions and leopards. It is our untamed thought, capable of circus tricks when trained with care. In his paintings, the zebra stands beside humans in acrobatic poses, echoing Buddha’s river lesson: balance, support, and presence.

His Own Way of Creating Mastery Work

Tới’s choice of medium — watercolor on silk — is not a nod to cliché but a return to authenticity. Trained in oil painting, he studied European masters in books; But during the field trip offered by his university in 2015-2016, he had a chance seeing them in person in Europe. He was struck by their simplicity, raw, direct, and heartfelt.

He abandoned oil for the medium that felt most honest: watercolor. On silk, it becomes ethereal, demanding precision and patience. It mirrors his personality — light, calm, and meticulous.

Yet beneath the mastery lies accessibility. His stitched works, though profound, begin with simple acts: cutting and sewing. The truth of Buddhism, like his art, is available to all.

Tới’s philosophy continues to evolve. Let’s wait for his next exhibition with anticipation — knowing it will surprise us with visual and philosopical ideas.