Eight months after my last visit, I returned to Hanoi and found myself once again at Indochine House—this time guided by Tâm and Liên, whose company enriched my experience in the exhibition. The works of three artists left a deep impression on me: Khổng Đỗ Duy, Nguyễn Thế Hùng, and Ca Lê Thắng.

Their art speaks not only to the richness of Vietnamese heritage, but also to the evolving dialogue between tradition and modernity, shaped by each artist’s personal journey.

Khổng Đỗ Duy (b. 1987): Worship in a Modern Frame

In Vietnamese homes, it’s common to find a small altar for worship—a practice that resonates deeply with me, as my grandparents in Hong Kong share similar rituals.

On new moon days, full moon days, birthdays, and anniversaries, they light incense and offer fruits to the ancestors and deities, seeking blessings of peace, health, and abundance. These acts form a bridge between past and future, memory and hope, devotion and grace.

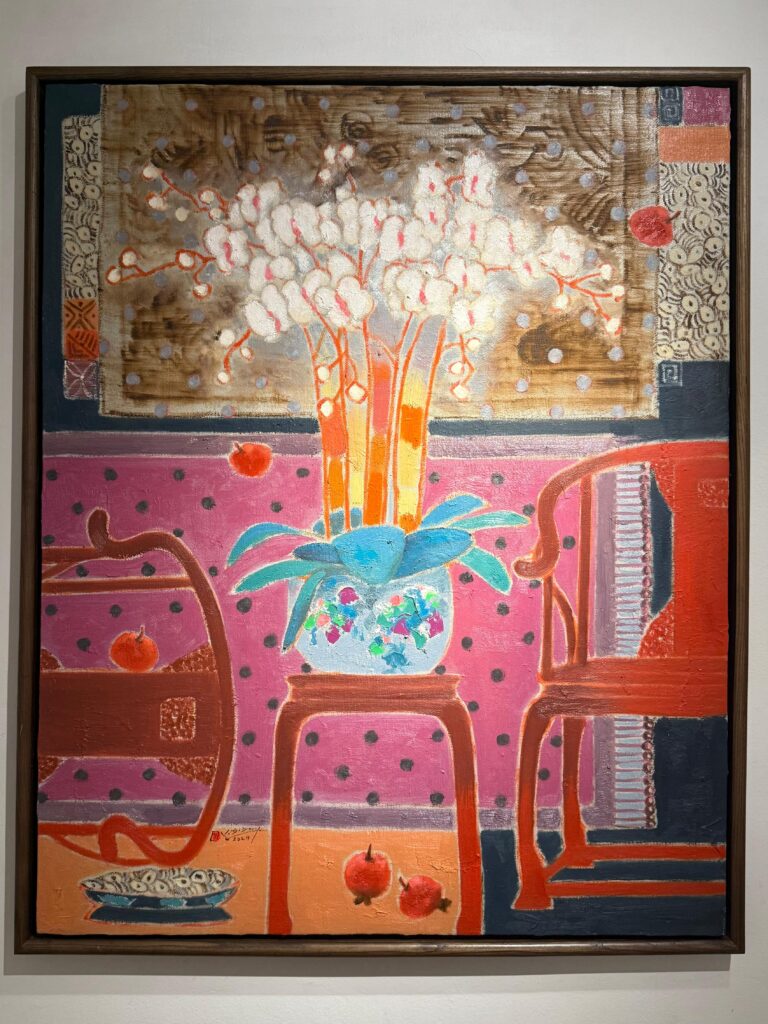

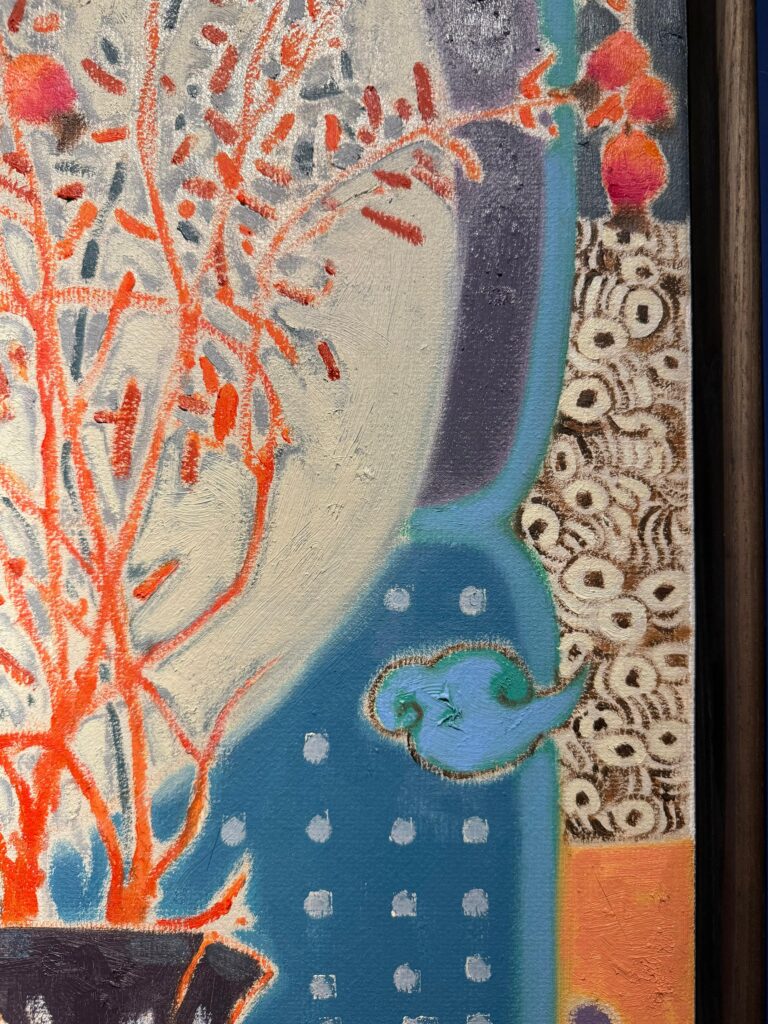

Khổng Đỗ Duy’s still-life paintings capture this essence with a contemporary twist. Set within domestic interiors, his works feature vibrant colours, flat perspectives, and an illusion of extended space that resembles rooms within rooms. The objects he paints—orchids, lilies, Buddha’s hand fruit, pomegranates, antique coins, five-coloured clouds, and ancient water motifs—are all symbols of traditional worship. Many are inspired by relics and museum artifacts, yet Duy reinterprets them through a modern lens.

While younger generations, including my own, may feel disconnected from these rituals, Duy’s work reminds us that heritage can evolve. Today, we worship technology like Apple, Google, Meta, replacing altars with screens. But perhaps, as Duy suggests, tradition need not be abandoned; it can be reimagined. Change is the only constant. His paintings offer a hopeful vision of cultural continuity.

A round Japanese Imari dish placed beside Duy’s paintings. Its colours, patterns, and circular form echo the visual language of his work, while also honouring Indochine House’s roots in dealing with works of art.

Nguyễn Thế Hùng (b. 1981): Lacquer as Ritual

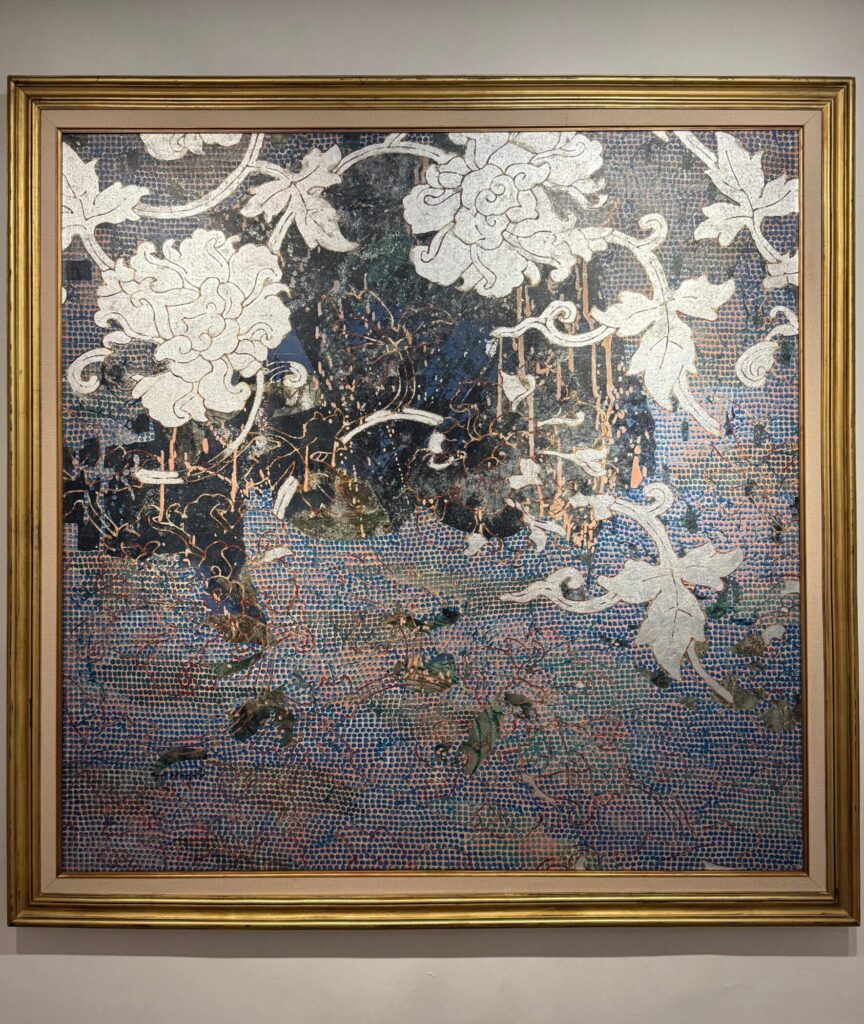

Nguyễn Thế Hùng’s work is a masterful blend of tradition and innovation. He extends the legacy of Vietnamese lacquer—once used in furniture and religious art—by applying it to canvas, merging Eastern technique with Western form. Though contemporary in approach, his process remains faithful to tradition: layer upon layer of lacquer is applied and meticulously sanded, revealing rich textures and subtle hues.

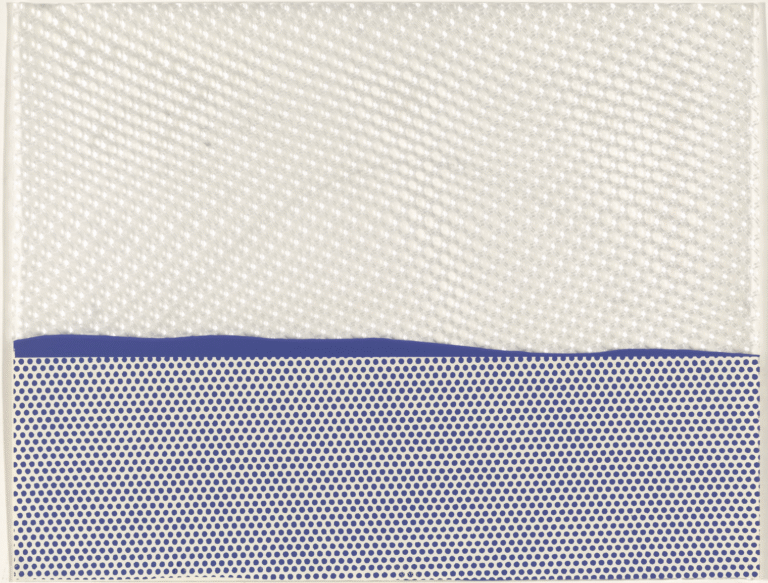

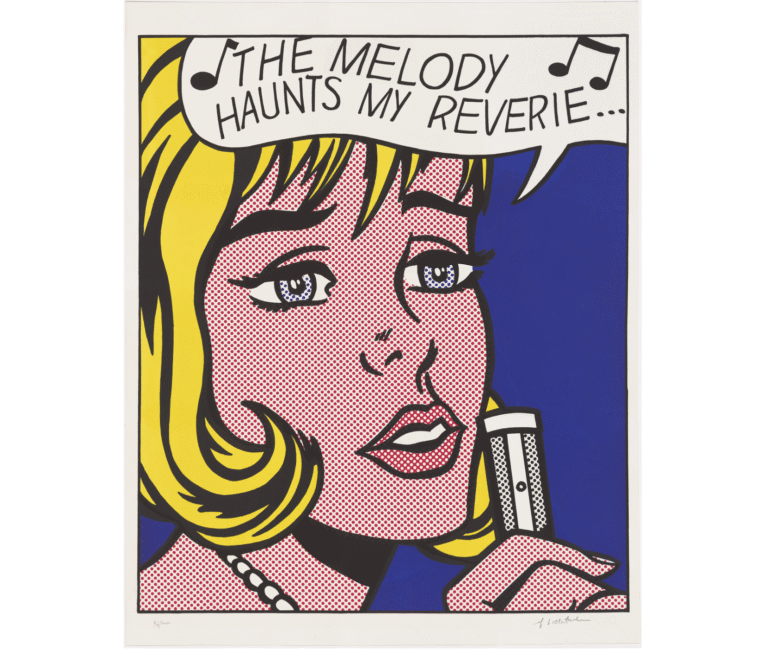

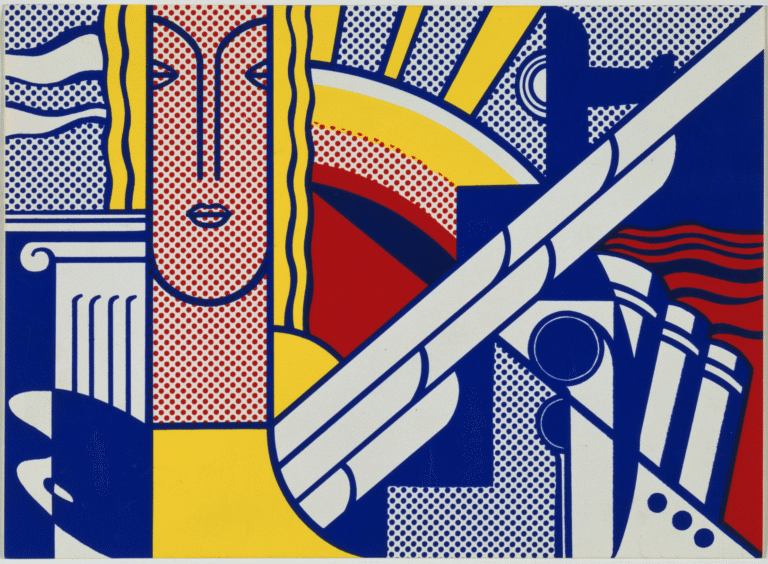

His canvases feel like sacred spaces. The hand-carved patterns recall temple architecture, while the tiny dots evoke pop art, reminiscent of Roy Lichtenstein’s industrial aesthetic. This contrast between spiritual craftsmanship and commercial art creates a compelling tension.

Hùng’s inspiration comes from nature—his treks with friends, the garden he tends at his studio. His art is meditative, rooted in the rhythms of the earth, and invites viewers into a quiet, contemplative world.

Ca Lê Thắng (b. 1949): Memory of the Mekong

Tâm’s favorite piece in the exhibition is Floating Season 2, part of Ca Lê Thắng’s Floating Season [Mùa Nước Nổi] series. Born in the Đồng Tháp Mười resistance zone in Southern Vietnam, Thắng moved to Hanoi at age six in 1955. His paintings are a tribute to the Mekong Delta during the floating season, when floodwaters bring life to the land—nourishing agriculture and fishing.

The landscapes are hauntingly serene, devoid of human presence. They capture a moment of peace before the turbulence of war. The water, in his work, becomes a metaphor for memory—submerging sorrow, longing, and the pain of displacement. After the war, Thắng returned to the South to teach at the Ho Chi Minh City University of Fine Arts from 1976 to 1988, reconnecting with the land that shaped him.

His paintings are not just landscapes; they are emotional geographies, mapping the distance between home and exile, past and present.